NAUTIA IN SHIMELBA

The Shimelba refugee camp in Ethiopia was chosen as the first case study to apply the NAUTIA methodology, as it is the smallest camp with the greatest needs.

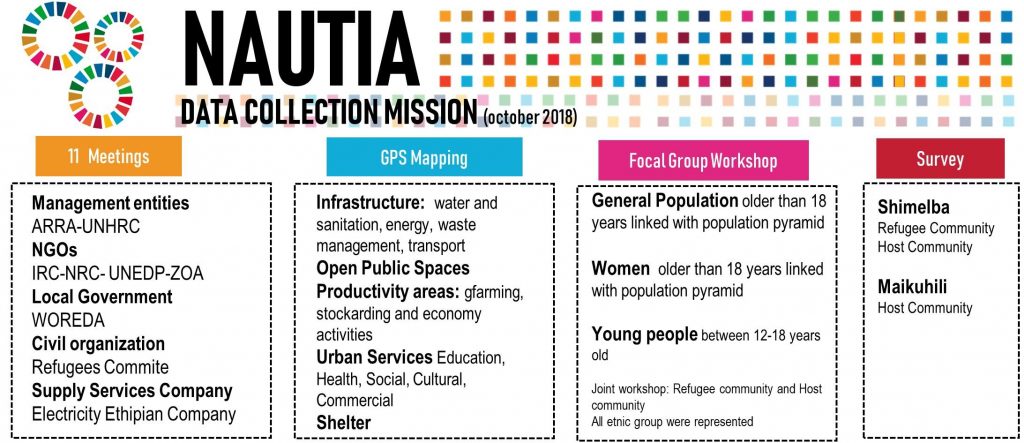

The data collection mission in Shimelba took place in October 2018. The task force included UPM researchers and members of Alianza Shire. The field work was coordinated by the ZOA team, who organized the logistics, validated the methodologies, and participated during implementation of the activities.

During the mission, interviews were conducted with the entities in charge of camp management and organizations operating in the area, as well as with the local government, the National Energy Supply Company, and the Refugee Committee. Three sessions of participatory workshops were held; two of which included the most vulnerable groups (women and minors under 18), while the third involved a sample of the general population. Both communities participated in the workshops, with the aim of fostering dialogue and social integration. During the spatial surveys, the settlements were mapped, and the information obtained from the bibliography was updated. Finally, surveys were conducted in both communities, which included all ethnic groups present in the sample group. The key findings are presented below, organized by sector.

RESULTS

Simbología Fotografías:

Comunidad de Refugiados

Comunidad de Acogida

In this area, aspects such as access, availability, quality and gender perspective in the provision of water and sanitation services are analysed. These items are also linked to the hygiene systems in place. Likewise, the current demand for water and sanitation is shown through the prioritisation of these services by the population.

The population of the refugee camp and the host community have access to adequate amounts of water (30–40 litres per day). According to the local leaders and authorities, the water comes from sources which are adequate for human consumption and irrigation of crops. The identified water points are located in public spaces such as schools.

The majority of refugees have latrines in their homes (81% of respondents). However, in the host community, less than half of the population (only 46% of respondents) have latrines at home. The rest of the population defecates outdoors because there are no communal use latrines. There are only latrines for public use in public infrastructures, such as schools and health facilities, among others, and these are mostly separated by sex (59% in the refugee camp and 67% in the host community). Regarding the quality of the latrines used by the refugee population, more than half of them (55%) are considered adequate because they have roofs and walls, a door that closes properly, a mosquito net, a slab and lighting. The quality of household latrines of the host community was not evaluated.

Access to systems of hand-washing and sanitary napkin disposal is limited in both cases (23% in the refugee camp and 5% in the host community). In addition, there is no wastewater treatment system. Regarding the demand for water and sanitation services, the refugee population prioritises water services over sanitation, whereas neither of the two services is prioritised by the host community.

Energy is an essential factor in addressing poverty. However, this resource is much more limited in rural contexts with lowincome levels, limited or inexistent possibilities of employment and opportunities to set up a business, and where the struggle for available resources (firewood) is one of the main causes of social conflicts and deforestation. In Shimelba, only 5% of the refugee population has access to electricity, on average 6 hours a day, through isolated diesel generators.Their operation is conditioned by the availability of fuel in the area and the owners’ ability to do the maintenance work. The host community is connected to the electrical grid, the electricity is generated by 99% renewable sources (conventional hydroelectric) and has a service of 18 or more hours per day.

The resource used to generate electricity directly influences the price for users. For refugees, electricity is not affordable since it represents 15% of a family’s income per month. Meanwhile, the host community spends only 5% of their income on this service. In a country with the climate of Ethiopia, electricity is considered affordable if the costs do not exceed 10% of the household income.

In terms of electricity services, the differences are also substantial. Energy services are very basic in the refugee camp: for lighting and charging mobile phones with a maximum consumption of 100Wh per day per family. The host community uses medium and high consumption appliances (fridges) and it records consumptions of 3.5kWh per day. Intervening in energy is a priority in the Shimelba refugee camp, not only to increase access to electricity but also to reduce the existing social gaps in comparison with the host community.

As in the refugee camp, the host population uses firewood and charcoal for cooking, and 60% of the population, mainly women, travel long distances to gather firewood. The consumption of firewood and charcoal affects mainly the health of women, children and the elderly, who are the ones who spend the most time at home.

Public lighting installations do not work, forcing women to stay at home for fear of situations of sexual and gender-based violence, especially at night. Having access to outdoor lighting systems is one of the great needs to be solved both for the refugee population and for the host community.

In terms of urban planning, the refugee camp has a better degree of planning than the host community, which sits mostly in a scattered manner. Shimelba does not have defined boundaries so integration with the host community in urban terms is simple. In fact, the host community has moved to the surroundings of the camp, and has increased in population. Only in Maikuhili, 8km from Shimelba, there is a rural settlement with a population of 200 people. The urban settlement pattern of Shimelba, set up on two perpendicular axes, is coordinated by ARRA, which uses the compounds as a multi-family plot unit. In both communities, the settlements lack paved surfaces and drainage networks to channel rainwater, which also makes mobility difficult in the settlement.

Internal journeys are mainly carried out on foot and supported by pack animals (donkeys or camels) and external displacements by bus to the nearest town of Shiraro.

The planning of Shimelba, unlike for the host community, does not include areas of public use. Therefore, the referred to public spaces are informal open spaces without any type of conditioning or design. This limits the hours of their usage for leisure due to the high temperatures reached at midday. In both settlements, the existing public space is used for commercial and sports activities.

Lastly, social awareness on waste management is very high in both communities. There are no garbage problems in the settlements. However, among the refugee population, waste management is not considered a priority, contrary to the opinion of the host population.

In terms of food security, the results show a reality marked by a deficiency in the intake of food of animal origin, high dependence on basic food supplies by the refugee population, and high vulnerability in a context of regional climate change, both in the case of the host population and the refugee population. Although the agricultural sector in Ethiopia is one of the most important for the country, from the point of view of the high volume of workforce involved in the same strategic interest, the reality observed in Shimelba and its surroundings shows a sector highly vulnerable to desertification and extreme weather.

Agricultural production in the area is one of the most important activities; sorghum (Sorghum spp.) is the main crop, followed by sesame (Sesamum indicum L), which is destined for export.

The presence of the Kunama population in Shimelba is a potential positive element for the implementation of strategies that lead to greater food production in the camp. By tradition, this population group has basic knowledge to cultivate the land and raise livestock. The presence of an area assigned for cultivation of vegetables and some fruit trees (papaya and mango) for self-consumption in the refugee camp stands out. This space is cultivated with hand tools. Irrigation is applied on the surface and by ploughing thanks to the presence of a few plants already in place.

The lack of intake of products of animal origin raises the question of including the raising of livestock in any proposal to improve food security. Moreover, in turn, this would result in production of manure with fertilising properties.

There are synergies with other sectors, such as obtaining biomass as an energy source. The increase in deforestation, together with the prohibition of firewood gathering by the refugee population, reveals their need of obtaining resources for cooking. This situation leads to the sale of food (some of it items from the humanitarian aid basket) to obtain these resources in the internal market of the camp.

Shimelba has two primary schools (one for the refugee population and one for the host community), a secondary school shared by both populations, a health centre and a centre for those with mental health problems. It also has an open space for the Friday market, fenced spaces for a children’s playground, a library, several churches (Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant) and mosques, a recreational centre and a volleyball court, in addition to the free spaces spontaneously occupied by children and their games.

It is in elementary schools where the disparities between both communities are more evident because the school buildings for the refugee population are in better conditions than those of the host population. In the latter, 50% of the modules lack roofs and some classes are taught in improvised classrooms.

However, overcrowded classrooms are more frequent in the refugee community, with 80 students per class. In the host community, that proportion drops to 50. The students, who participated in one of the workshops, asked mainly for classrooms, electricity, uniforms and books for their schools.

The refugee camp does not currently have a vocational training centre, despite the fact that the population needs it. In Maikuhili, however, there is a Training Centre in Agriculture. Education is rated among the top five priorities by both populations.

Furthermore, it is striking that despite having health centres both in the refugee camp and in the host community of Maikuhili, the populations, especially the refugees, consider access to health services as a priority. The nearest hospital is in Shire, two and a half hours by road, and women identify the local health centres as unsafe spaces.

Regarding communication technologies, more than 50% of both populations have a smartphone, despite the fact that data coverage is very poor in the refugee camp. For the host population, unlike the refugees, access to Internet is among the top five priorities, although there are almost no laptops or tablets, let alone Internet centres that facilitate access to them.

Both in Shimelba and in its host community, dimensions of the plots are more suitable for a rural environment than an urban one and are delimited by permeable plant elements or walls made of clay. Both communities have subsistence crops and livestock inside their plots. Spaces of private use are shared between people and livestock, which results in generation of health problems.

Shimelba is composed of 4,436 households, with an average of 5.25 people living in each one. In the case of the host community, the average drops to 4.45. Building materials used by the refugee community are plant fibres for the roof and clay for the vertical elements, while the host community uses zinc sheets and cement. In both communities, self-construction is the building mean used.

In qualitative terms, the refugee population is in a worse situation than the host community. The difference in building quality is the main factor of disparity because of the lack of durability of the structures. 85% of the refugee shelters do not meet the essential requirements of habitability. The refugee population does not have access to adequate construction materials and construction techniques are not well implemented. Consequently, shelters do not have watertight roofs and walls must be renovated annually.

Consequently, 80% of the shelters in the camp are vulnerable to inclement weather such as rain and wind, in comparison with 20% in the host community. For this reason, the refugee population considers that improvement of housing is a priority, and in particular, the adaptation of walls and roofs. Moreover, solar radiation is the main cause of excessive temperatures inside the houses. The material used by the host community, despite its greater durability, causes overheating problems.